Tomorrow’s Organization Design Forum’s peer-to-peer consulting session in which I’m in the hot-seat has been drifting to front-of-mind over the last couple of weeks: prompted by first, a coaching session on how to frame the question in a way that the peer group can tackle it, and then by getting a Zoom invite to the actual session that proved to me that I’m actually in the hot seat.

The way it works is rather like a fish-bowl exercise, but virtually. I sit in the ‘middle’, and briefly outline my conundrum. Five consultants the discuss it. We follow the ‘Ace-It’ formula. Other people ‘watch’ the session in action, commenting only via the chat box.

The info that has gone to the five consultants says: ‘The ask for Naomi to hold this session came out of a high level of interest shared during one of our monthly virtual conversations (ODF Advisory Group) around an article she wrote Accountability – Is it a Design Concern? featured in EODF’s monthly newsletter. People suggested that I do a follow-up blog but it turned into this live session instead.

The conundrum I’m posing to the consultants is:

Work process flows almost always cross organizational boundaries, either internal boundaries or between organization boundaries. This can create difficulties, bottlenecks, and failure points at the intersects and hand-overs. Assigning a single person accountability for the process flow does not allow for the fact that the accountable person may not have control over the people along the flow. These people may be working on other flows, have different priorities, and different performance measures. Along the flow, people may have the power to slow or stop the flow.

Imagine a design that assumed a collective accountability to maintain process flow. How could this be designed?

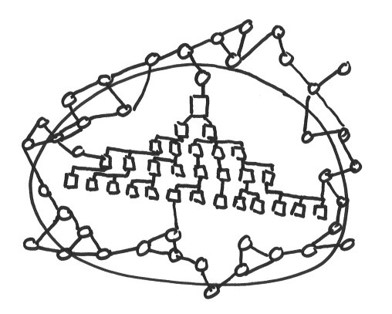

Last week I wrote a blog and also ran a session on Hierarchies and Networks. In these two forums I asked whether ‘the very differently principled networks and hierarchies co-exist in one organization’? I think they do, along with the informal networks that are in both.

In response to that blog Nicolay Worren sent me his excellent – still in draft – paper The “hidden matrix”: Reporting relationships outside the formal line organization. In this, he talks about some research in which he has found that ‘Even though the organization does not formally have a matrix organization, the decision rights have been distributed in such a manner that employees will require the approval of people who are not their line manager, who is outside their own department, and may not be hierarchically superior to themselves.’

He is wondering, similarly to me, about mixing of structures in one organization – one of which is often consciously designed (the hierarchy) and the other which equally formal but not usually consciously designed – the network or, in Worren’s case, the matrix. He doesn’t speak much about the informal networks in both.

I’m intrigued to find that a network can be expressed mathematically as a matrix but I’m not going to pursue the difference between them in organizational design terms right now. Another intriguing take is in the article To Matrix, Hierarchy or Network: that is the question. It’s not directly about organization design but there are great parallels that might be usable in design work.

Pursuing the network route for now, RAND researcher, Paul Baran, began thinking about the optimal structure of the Internet. He envisioned a network of unmanned nodes that would act as switches, routing information from one node to another to their final destinations. Baran suggested there were three possible architectures for such a network —centralized, decentralized, and distributed.

He felt the first two —centralized and decentralized— were vulnerable to attack, the third distributed or mesh-like structure would be more resilient. And this is what he designed. The Internet is a network of routers that communicate with each other through protocols – which might be an organizational proxy for decision rights, approvals, and distributed accountability.

The mesh like structure is what I think of when I think of networks, and I dug out my blog Of Nets and Networks and found that the metaphor of accountability exists in physical fishing nets. Each knot in the net is ‘accountable’ for the success of each other part of the net. The knots are representative of shared and distributed accountability. The way the fishermen work with the nets represents the informal network. But maybe I’m carrying that too far?

Then my brother sent me a snippet that seemed to perfectly describe organizational networks – formal and informal in one go. Except it was referring to consciousness:

‘In our brains there is a cobbled-together collection of specialist brain circuits, which, thanks to a family of habits inculcated partly by culture and partly by individual self-exploration, conspire together to produce a more or less orderly, more or less effective, more or less well-designed virtual machine, the Joycean machine. By yoking these independently evolved specialist organs together in common cause, and thereby giving their union vastly enhanced powers, this virtual machine, this software of the brain, performs a sort of internal political miracle: It creates a virtual captain of the crew, without elevating any one of them to long-term dictatorial power. Who’s in charge? First one coalition, then another…’ It’s from Daniel Dennett, (1991) Consciousness Explained, Little, Brown and Co.

I’m not sure how all this rumination has progressed my thinking on organizational networks and distributed accountability, in a way that will make sense when I sit in the hot seat tomorrow. But it’s been an interesting exploration. Do you think networks distribute accountability? Let me know.